Response Planning

Last Updated: August 2022

Prepare for the outbreak by first developing a response plan. Determine who is responsible for detecting and responding to an outbreak and which systems play an integral role. Consider the following stakeholders and systems included in the list below. Many of these areas are expanded upon in other sections of this toolkit.

Mechanisms for Detecting an Overdose Anomaly

Detecting an anomaly of drug overdoses can be challenging, especially distinguishing a short-term transient spike from a sustained increase. The following steps and considerations can guide a jurisdiction in detecting an overdose anomaly.

1.) Understand How an Anomaly Reporting May Occur

Traditional surveillance systems may be monitored to detect increases. Some examples include :

- Syndromic surveillance systems report changes in conditions

- Local poisoning center reports sharp increase in calls

- Enhanced medical examiner or coroner surveillance, such as SUDORS, captures emerging threats through enhanced toxicology testing and changing polysubstance use patterns (e.g., increases in co-use of opioids and methamphetamines or opioids and benzodiazepines), or a sharp increase in illicit opioid use (e.g., pill mill closed and spike in heroin deaths among previous patients)

- Surveillance of fatal overdoses notes similarities in drug type

Informal Reporting methods rely on anecdotal reports and perceived trend impressions from partners.

- Increase in 911 calls related to overdose – The quality of this indicator varies across jurisdictions due to differences in data collection procedures and variables. Check with the affected jurisdiction about the utility of this data.

- Sharp increase in EMS treating suspected overdoses and reversing opioid overdoses with naloxone.

- Hospital emergency departments report large numbers of overdoses presenting.

- The police reports an increase in illicit drug seizures or rapid increases in illicit drug seizures containing a new type of synthetic opioid such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, or other synthetic opioids such as U-47700.

- ME/Cs noting a sharp increase in overdose deaths.

2.) Identify Available Data Sources and Surveillance Systems

| Data Source | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| NSSP | Syndromic surveillance data received from emergency departments, urgent and ambulatory care centers, inpatient healthcare settings, and laboratories |

| State Syndromic Surveillance Systems | Syndromic systems developed outside and used separately from NSSP’s BioSense Platform and Electronic Surveillance System for Early Notification of Community-based Epidemics (ESSENCE) |

| Emergency Medical Systems | Data includes services that are provided outside of the hospital setting that includes transport to care facilities – systems include the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) and bioSpatial. |

| Medical Examiners and Coroners (ME/C) | Includes post-mortem toxicology testing finding, medical history, drug use history, and death scene investigation. |

| State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS) | Abstracts data from ME/C reports and integrates with death certificate data and toxicology reports |

| Prescribing Systems | Physician prescribing databases including IQVIA, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMP), and Prescription Behavior Surveillance System (PBSS) |

| Poison Center Data | Information about specific agents or clinical management guidance about suspected or known chemical, drug, and other exposures. |

| State Police Data | Drug seizure investigation data |

| High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) | First responder data for drug trafficking and use of illegal drugs, related to violent crime and money laundering |

| Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMAP) | A free, web-based software platform to support reporting and surveillance of fatal and nonfatal drug overdoses |

| Syringe Service Programs | Information regarding new trends and substances |

3.) Develop Activation Thresholds

- Identify thresholds for what constitutes an anomaly. These thresholds should be established by the jurisdiction where it will be applied and can vary between jurisdictions.

- Create a process for validating the outbreak and reducing the chance it is caused by a data quality error:

- Plan to have communication with partners that monitor other near real-time data to evaluate their sources and corroborate consistent increases.

- Consider tools such as Smartsheet, MS Teams, REDCap, or other web-based methods to centralize and share confidential information quickly rather than using email.

- Develop a decision tree that determines when an anomaly will activate a response

- Establish a fixed activation threshold may be difficult, consider the following factors:

- Current program response capacity

- A threshold number of overdoses that would exceed program response capacity and indicate the need for additional resources

- Consider the frequency of alerts that can be responded to avoid alert fatigue or overly tax resources. Set thresholds based on historic frequency that does not occur often, such as a peak number of overdoses seen only once a month.

- Low burden areas may want to monitor counts of overdoses over longer time frames. High burden areas may have enough power to detect increases daily or can use percent increases to adjust for changing total volume of visits reported.

- Consider which agencies or programs can provide the additional resources

- Example: Pennsylvania EpiCenter Alert Guidance: Thresholds for suspected overdose by facility location and by home location

4.) Define Overdose Anomaly

Based on the information gathered, investigators can determine if an increase in overdose deaths is a:

- General gradual increase in overdoses occurring steadily over time

- In the case of opioid use this type of increase may be a consequence of persistent changes over time in prescriptions for opioids, changes in polysubstance use patterns, increases in opioid use disorder (OUD) or changes in the type of opioid misused. Examples include:

- Limited increase in overdoses in a narrow geographic area and/or time frame – the spike or extremely high community burden may be identified as:

- A change in the illicit drug supply linked to a very limited source (e.g., tainted supply from one illicit drug dealer or supplier) or geographic areas. These types of spikes may rapidly turn into widespread outbreaks. Here are examples in California, Connecticut, Georgia, and West Virginia.

- Related to exceptionally high levels of inappropriate prescribing of opioid pain relievers or other controlled substances in a specific geographic area. See example in Staten Island, New York City.

- Related to a single clinical provider.

- Widespread outbreak impacting a large geographic area :

- An increase in overdose deaths identified as an outbreak are characterized by widespread changes in the illicit drug supply and use patterns and/or widespread changes in prescription, diversion, or misuse of prescription drugs.

- Here are examples of widespread fentanyl and fentanyl analog outbreaks across multiple states as well as widespread state outbreaks in Florida, Ohio, and Massachusetts.

5.) Set Investigation Goals

Below are some examples of investigation goals you may consider when designing your inquiry.

- Determine the extent of the outbreak and how long the outbreak has been occurring

- Note that identification of outbreaks occurs once a number of cases have already been detected, especially in scenarios where overdoses may spike rapidly

- Identify key changes in risk factors for overdose or opioid-related harms

- Understand similarities or connections among cases

- Implement and evaluate interventions to rapidly reduce the incidence of overdoses and the proportion of overdoses that are fatal

- Rapid interventions could target known risk factors such as recent release from an institution and/or risk factors unique to the outbreak (e.g., specific group disproportionately affected by cocaine contaminated with fentanyl)

- Increase access to medication for opiod use disorder MOUD and linkage of high-risk individuals to treatment and harm reduction services, such as people with opioid use disorder released from incarceration, people seeking treatment at the ED for an opioid overdose, and people injecting drugs or using illicit opioids such as heroin or fentanyl.

- Support and enhance current systems:

- Healthcare

- Community Partners

- Surveillance

- Law Enforcement

- ME/C

- Public messaging and health communication

6.) Develop an Incident Action Plan

An incident action plan (IAP) formally documents incident goals, operational period objectives, and the response strategy defined by incident command during response planning. It contains general tactics to achieve goals and objectives within the overall strategy, while providing important information on event and response parameters. Equally important, the IAP facilitates dissemination of critical information about the status of response assets themselves. Because incident parameters evolve, action plans must be revised on a regular basis (at least once per operational period) to maintain consistent, up-to-date guidance across the system.

- DHHS What is an Incident Action Plan?

- IAP Example – Montgomery County, Ohio

7.) Decide when the Anomaly is Over

- Determine what measures should be taken for further monitoring to ensure the outbreak remains resolved. Continue collaboration with neighboring jurisdictions if needed.

- Determine what measures should be taken for further monitoring to ensure the outbreak remains resolved or enhanced sustained response to the endemic problem.

- Identify opportunities for long-term community capacity-building to prevent and address future outbreaks.

Response Plan Templates

After identifying the putative source of the outbreak, begin considering what would be an appropriate public health response. When formulating a response plan, consider what other organizations have done and have learned from their experiences. Here are some examples to consider:

- Ohio Department of Health Community Response Plan Template

- ODMAP Overdose Spike Response Framework

- Indiana Overdose Response Toolkit

- North Carolina Opioid Action Plan

- NACCHO – Opioid Overdose Epidemic Toolkit for Local Health Departments

- NACCHO – Environmental Scan of Local Health Department Approaches to Opioid Use Prevention and Response

- ASTHO – Responding to an Overdose Spike Guide

- NACCHO – Overdose Spike Response Framework for Communities and Local Health Departments

Stakeholders

Detecting and responding to overdose events requires a multidisciplinary team of stakeholders who each contribute to different aspects of the plan – investigation, response, and evaluation. Building such a team will require networking with many different organizations within the jurisdiction to cover all the aspects of partnership needed. The sections below list some stakeholders and other partners that have been key participants in jurisdictions’ efforts to address overdose.

Leadership

Determine who provides leadership and oversight of response activities. Traditionally, this is the responsibility of state, local, territorial, or tribal health departments. Also determine who is responsible for coordinating activities of internal and external partners.

Surveillance

Determine the available surveillance systems and ongoing surveillance activities in the jurisdiction. Other questions to consider:

- Who manages data and conducts informatics-related activities?

- Who conducts data-collection activities such as interviews of affected individuals or stakeholders?

- When are contact investigations and contact tracing conducted? Who is responsible for conducting investigations if needed?

- Who coordinates data availability among systems?

- Who analyzes the data and detects the outbreak?

Laboratory

Determine who provides laboratory support for drug testing and infectious-related complications (HIV, HCV) and where the laboratories are located. What is the surge capacity of the lab? What testing can the lab provide i.e., immunoassay or comprehensive testing?

Communications

Determine who conducts communication activities to internal stakeholders, the community, and the media. Consider who will coordinate the messaging and who will develop the messages both for internal and external stakeholders. Determine how messages will be reviewed and by whom prior to release. It is important to integrate lessons learned from previous communication efforts such as not identifying specific locations and stressing drug toxicity versus potency.

Response Measures

Questions to consider for response measures:

- Who implements control and overdose prevention measures?

- Who provides harm reduction services?

- Who provides substance use disorder treatment and behavioral health services?

Wrap-around Services

Determine who will provide or support the following services:

- Health care access

- Behavioral and mental health care access

- Vocational training and education opportunities

- Employment Services

- Family Services

- Housing

- Transportation

Response Staff

Identify resources for response staff from other local, state, territorial, tribal, federal agencies. For example, for opioid overdose consider reaching out to CDC for an Epi-Aid or to the Opioid Rapid Response Program.

Incident Command Structure

Develop an incident command structure framework for an overdose outbreak response (see Toolkit Resources) for example frameworks. Determine what are legal authorities for a response. Also consider this primer prepared by GHHS here.

Healthcare Providers

Develop and frequently update lists of providers for:

- Substance use disorders

- HIV; Hepatitis B and C

- Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS)

- Drug Treatment Facilities

Regulations and Policies

Review relevant state and local opioid-related policies and regulations including the following:

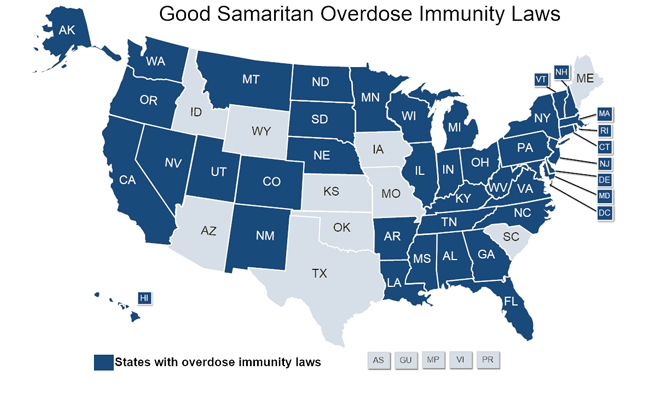

- Good Samaritan laws

- Naloxone distribution laws

- Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD)

Figure 1. Good Samaritan Overdose Immunity Laws. Source: National Conference of State Legislatures.

Public Health Response Team

Educate all public health responders about commonly abused drugs and persons who inject drugs. CDC developed a training guide for responders to provide information about the overdose crisis. Training access instructions are available on CDC’s website.

Toolkit Resources

Get more insights by using our toolkit resources.

Go to Resources

Glossary

Learn the definition of the key words being used.

Go to Glossary

Thanks

Thank you, to all of our contributors.

View our contributors

the public’s health.

Contact Us

Have any questions or recommendations, you can contact us at overdose@cste.org